Smoking and Tobacco

The Marijuana Sex Experiment

1975: There was a public hoo-ha when details of Dr. Harris Rubin's planned "marijuana sex study" leaked to the press. As described in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Dec 7, 1975):The New Scientist noted that, despite the moral outrage, the purpose of the study was actually to generate anti-marijuana propaganda by demonstrating that marijuana inhibits sexual response. At least, that was the anticipated result. But the experiment was never conducted.

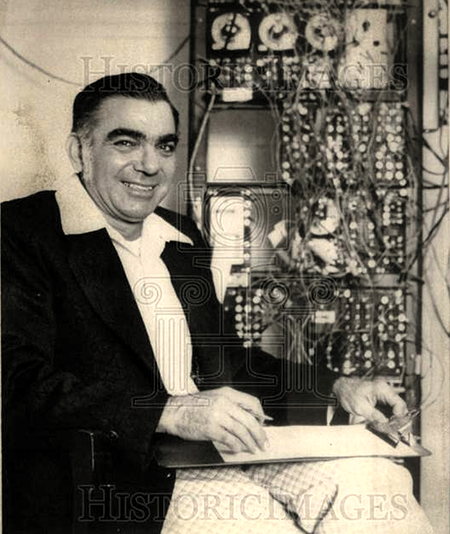

Dr. Harris Rubin of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine at Carbondale

Morton Hunt gives more details in his 1999 book The New Know-Nothings:

On July 18, the Bloomington, Illinois, Daily Pantagraph, which had somehow become aware of the study, ran an article about it, and from then on Rubin's project was in trouble. Newspapers in Illinois, St. Louis, Washington, Chicago, and many other cities ran stories about what quickly became known as the "sex-pot study" or "pot-sex study," a topic so interesting that they ran follow-up stories about it for many months. Displaying suitable outrage, the Christian Citizens Lobby, Illinois governor Daniel Walker, a federal prosecutor, and various Illinois state officials all denounced the study, calling it "disgusing," "pornography," "obscene," and "garbage," and threatening to take action against Rubin.

This was mere growling and snapping, but Congress had the teeth wherewith to bite. Senators William Proxmire and Thomas Eagleton, Democrats but sexual conservatives, attacked it, as did Representative Robert Michel, the ranking Republican member of the House Appropriations subcommittee. Although the secretary of HEW and the president's National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse defended and supported the project, Michel sought to prevent NIDA from funding the Rubin study by tucking an amendment to that effect in the $12.7 billion-dollar 1976 Supplemental Appropriations Bill for HEW, and Senators Proxmire and Warren Magnuson inserted a similar provision into the Senate's version of the bill. The funding of HEW was so crucial to the national well-being that both houses passed the bill with the anti-Rubin provision intact. President Ford signed it into law on May 31, 1976, keeping the vast Social Security system, NIH, and other essential endeavors going—and cutting off Rubin's minuscule funding and putting an end to his research. Rubin had already gathered the alcohol data and he eventually published his results, but the marijuana study died a-borning.

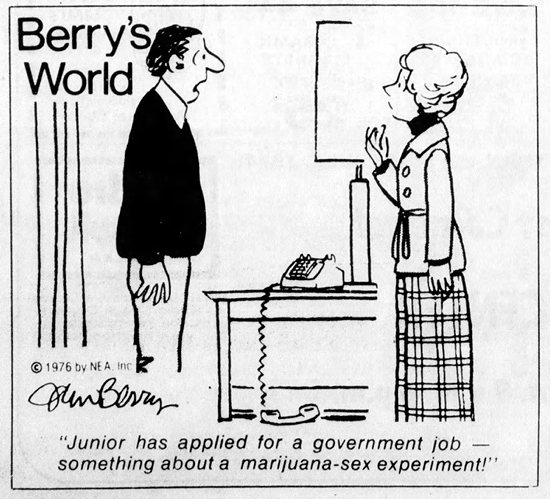

The Sedalia Democrat - Feb 4, 1976

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jul 31, 2021 -

Comments (6)

Category: Drugs, Smoking and Tobacco, Experiments, 1970s, Moral Panics and Public Hysteria

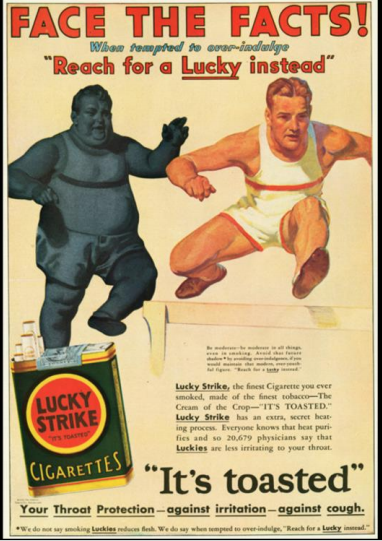

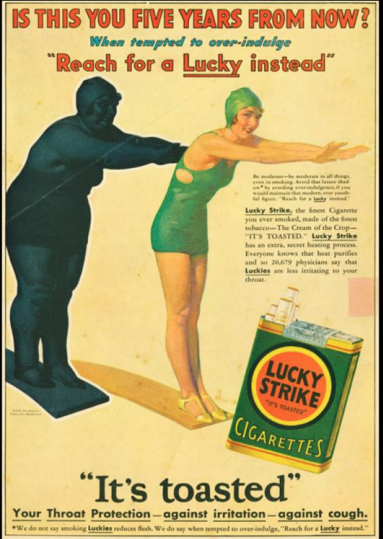

Lucky Strikes as Weight-Loss Aid

See more in this series at the link.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 26, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Advertising, Smoking and Tobacco, Twentieth Century, Dieting and Weight Loss

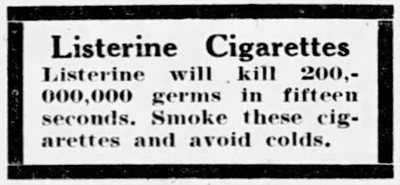

Listerine Cigarettes

Another case of an odd brand extension. In 1927, the manufacturer of Listerine debuted Listerine Cigarettes that were infused with the same antiseptic oils used in the mouthwash.The company claimed that these cigarettes would not only "soothe the delicate membranes of mouth and throat," just like the mouthwash, but also that they would "kill 200,000,000 germs in fifteen seconds" and help smokers avoid colds.

As far as I can tell, Listerine Cigarettes remained on the market until the mid-1930s and then disappeared.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch - Dec 12, 1927

Tampa Tribune - Nov 8, 1930

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 19, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Health, Cures for the common cold, Smoking and Tobacco

The Safety Smoker

The "safety smoker," invented by Glen R. Foote of Cincinnati, promised to allow people to safely smoke "in places where the danger from flying or falling sparks is likely to start a conflagration or cause an explosion."Perfect for anyone hankering for a smoke in an oil refinery.

San Francisco Examiner - Jan 1, 1933

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 07, 2021 -

Comments (6)

Category: Inventions, Smoking and Tobacco, 1930s

Dr. Munch’s Marijuana Madness

1938: Dr. James Clyde Munch described to his students at Temple University what happened when he smoked "a handful of reefers" as an experiment.I'm thinking there may have been something more than just marijuana in those cigarettes.

Time - Apr 11, 1938

Munch liked his story about the disorienting effects of marijuana so much that he repeated it at several criminal trials.

New York Daily News - Apr 8, 1938

Posted By: Alex - Fri May 14, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Drugs, Smoking and Tobacco, Experiments, 1930s

Cigarette lighter that gives the finger

In 1942, George Horther was granted a patent for what he called an "electric resistance lighter". From what I can gather, lifting the finger activated the lighter. He had received a separate design patent in 1940 for the invention's appearance.

Curiously, in neither patent did Horther ever refer to the significance of the gesture his invention is making, even though that's pretty much the entire point of it.

I imagine he must have intended to sell this as a gag gift, but I can't find any evidence that he ever did manage to market it.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 18, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Smoking and Tobacco, 1940s

Fire-Breathing Woman

In April 1940, Linda Lancaster Dodge Stratton was granted a patent for the "cigar or cigarette lighter" shown below. Its novel feature was that it was shaped like a fire-breathing woman. Or, as Stratton put it, "in the shape of a human figure artistically posed with the igniting means located in the mouth and ignited and extinguished by the movement of the head to open and close the mouth thereof through the manual movement of the arms toward and from the mouth."It kinda looks like a fire-breathing Barbie. Though it predates Barbie by almost 20 years.

The patent said this woman was to be "constructed in a pocket or a table size." It would definitely be a conversation piece to have a table-size version of her in your home.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 04, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Smoking and Tobacco, 1940s, Women

Cheese-Filtered Cigarettes

We've previously posted about "cheese candy", which was the invention of Wisconsin lumberman Stuart Stebbings. Another of his inventions was cheese-filtered cigarettes. He was, apparently, a man driven to find new uses for cheese.

Lab tests demonstrated that a cheese filter could remove 90 percent of the tar in cigarettes. A hard cheese worked best, such as Parmesan, Romano, or Swiss. Although an aged cheddar could also be used. Or even a blend of cheeses.

In 1966, Stebbings was granted Patent No. 3,234,948. But as far as I know, his cheese-filtered cigarettes never made it to market.

Mason City Globe-Gazette - Feb 8, 1960

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jan 03, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Food, Inventions, Patents, Smoking and Tobacco, 1960s

Kent, the asbestos-filtered cigarette

In 1952, in response to growing concerns about the safety of cigarettes, the Lorillard Tobacco Company introduced Kent cigarettes, boasting that they contained a "Micronite filter" developed by "researchers in atomic energy plants".Turned out that the key ingredient in the Micronite filter was asbestos. From wikipedia:

According to Mother Jones, the company is still battling lawsuits to this day.

Chicago Tribune - Apr 1, 1952

Posted By: Alex - Mon Dec 14, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Health, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Smoking and Tobacco, 1950s

“Perfect smoke column from end to end”

The model looks slightly out-of-it as the "Accu-Ray" machine deposits an endless supply of cigarettes into her hand. Perhaps, like James Bond, she had a 70-cigarette-a-day habit that had to be constantly fed.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 23, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Advertising, Smoking and Tobacco, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |