Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy

Two Crazy Scientists

Posted By: Paul - Thu Nov 21, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Music, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, 1960s

Lunar Space Elevator

We've posted before about the space elevator concept — an elevator going from the surface of the Earth into orbit.It's not possible to build one with current technology. But what about a lunar space elevator? That's an elevator that would go from the surface of the moon into lunar orbit.

Spacecraft systems engineer Charles Radley argues that "A Lunar Space Elevator [LSE] can be built today from existing commercial polymers; manufactured, launched and deployed for less than $2B."

I'm guessing that dollar amount would need to be multiplied by about 100 to be closer to the actual amount.

More info: "The Lunar Space Elevator, a Near Term Means to Reduce Cost of Lunar Access"

source: wikipedia

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 12, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy

Terraforming Venus

If humans are ever going to colonize another planet in the Solar System, the obvious choice would be Mars. But a vocal minority has long made the case for Venus. They argue that Venus has one huge advantage over Mars — it has almost the same gravity as Earth.However, there's the problem of its scalding-hot temperature. Back in the early 1980s, French scientist Christian Marchal proposed a way to cool Venus by creating a giant cloud of dust between it and the sun.

Idaho Statesman - Oct 3, 1982

source: Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments (1995), by Martyn Fogg

Cooling Venus in this way might be doable, but critics have noted that, even if you succeeded in cooling it, Venus has no water, and you need water to get rid of the carbon in its atmosphere.

Marchal's supporters have subsequently expanded his idea by proposing that we could first hydrate Venus by bombarding it with hundreds of icy asteroids. Of course, doing this would significantly increase the difficulty and cost of the whole terraforming project.

Basically, none of us will ever live to see any of this happen.

More info: Marchal, "The Venus-new-world project," in Acta Astronautica, May–June 1983; "The Terraforming of Venus," by Martyn Fogg.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 24, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy

The Cellular Cosmogony

Here's your chance to learn the truth: that we are all living inside the Earth, rather than on top of its surface.The Wikipedia page for Koresh, aka Cyrus Teed.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 18, 2024 -

Comments (4)

Category: Eccentrics, Frauds, Cons and Scams, New Age, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Nineteenth Century

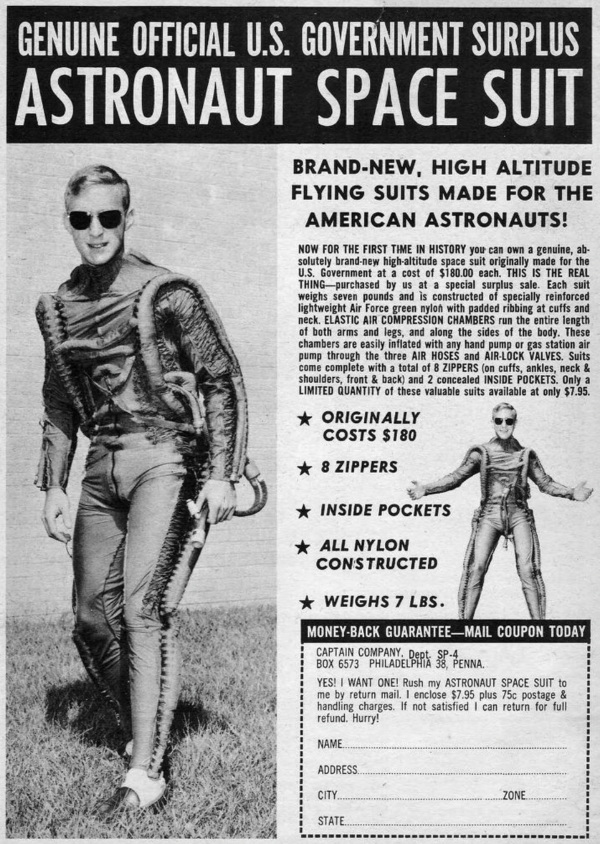

Astronaut Space Suit

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 20, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Fashion, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, 1960s

Are we swallowing other universes?

An unusual cosmological hypothesis was recently published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. At least, it's an idea I haven't heard before.It suggests that our universe has been swallowing "baby universes," and that this eating habit is the cause of the observed accelerating rate of expansion of our universe.

The article, authored by researchers from the Niels Bohr Institute and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, quickly veers off into mathematics that's incomprehensible to me. But I can extract a few interesting ideas. For instance, what if the initial "Big Bang" of our universe was caused by us (when we were still a baby universe) being swallowed by a larger universe?

And what would happen if, now that we're an adult universe, we collided with another adult universe? The researchers don't answer this question, but I'm guessing the outcome wouldn't be good.

More info: "Is the present acceleration of the Universe caused by merging with other universes?"

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 06, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Science, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Weird Theory

The Kendall Paracone

In the early years of the American space program there was a lot of concern about how to get stranded astronauts safely back to Earth. One idea was the "Kendall Paracone," proposed by Robert Kendall of McDonnell Douglass.Kendall imagined astronauts dropping from space back to earth inside of a giant, gas-inflatable shuttlecock. The shape of the shuttlecock would ensure that it always remained nose down, preventing the device from tipping over and roasting the astronaut during re-entry. It also required no parachute. It would simply plunge all the way to the ground, slowing down naturally from air resistance just as badminton shuttlecocks do. Shock absorbers in the nose would dampen the final impact.

Coos Bay World - Oct 29, 1976

"astronaut escape sequence"

"Techniques for space and hypersonic flight escape, SAE Transactions, Vol 76, Section 3

Kendall thought his paracone system could also stop helicopters from crashing:

Aeronautical Engineering - Jan 1978

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 01, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy

The One-Way Mission to the Moon

1962: Fearing that the Soviets were going to beat the United States to the moon, two engineers from Bell Aerosystems Company, John Cord and Leonard Seale, proposed a way to make sure America got there first. Their idea was to send an astronaut on a one-way mission to the moon. After all, it's a lot easier to send a man to the moon if you don't have to worry about bringing him back.They presented their idea at the meeting of the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences in Los Angeles and also published it in the Dec 1962 issue of Aerospace Engineering.

Read the entire article (pdf)

Their plan was for NASA to first land a series of unmanned cargo vehicles on the moon that would contain all the necessities for a lunar base. An astronaut would then make the journey to the moon and, after landing, assemble the base. Every month NASA would send a new cargo vehicle to resupply the astronaut with essentials — food, water, and oxygen. This would continue until NASA figured out a way to bring him back.

NASA, perhaps sensing that the public would perceive a one-way mission as an admission of defeat rather than a sign of victory, ignored the proposal.

Base for a one-way lunar mission

Although NASA ignored Cord and Seale's plan, it caught the attention of science-fiction writer Hank Searls, serving as the inspiration for his 1964 novel, The Pilgrim Project. Hollywood developed Searls' book into a 1968 movie, Countdown, directed by Robert Altman and starring James Caan and Robert Duvall.

In both the book and movie, NASA succeeds in landing an astronaut on the moon. The astronaut then discovers that the Soviets got there first — but all died.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Dec 06, 2023 -

Comments (8)

Category: Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, Space Travel, 1960s

The Chicken Astronaut

Posted By: Paul - Tue Nov 21, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Emotions, Courage, Bravery, Heroism and Valor, Music, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, 1960s

Bishop in Space

Nov 1957: Lord Alastair Graham offered a solution for declining church attendance. Launch a bishop into space inside a sputnik.For context, the Soviets had just a few days before (Nov 3, 1957) launched Sputnik 2 which carried the first living creature into space, a small dog named Laika. Graham's remark was evidently a reference to this.

However, while the Soviets had succeeded in getting Laika into space, they had made no plans for getting her back alive. It was a one-way trip. It's not clear that Graham realized this, but it definitely puts a different spin on his suggestion.

The Guardian - Nov 13, 1957

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 20, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Religion, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |