War

Tiniest North Korean Spy Caught!

Full story here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 15, 2013 -

Comments (5)

Category: War, 1950s, Asia

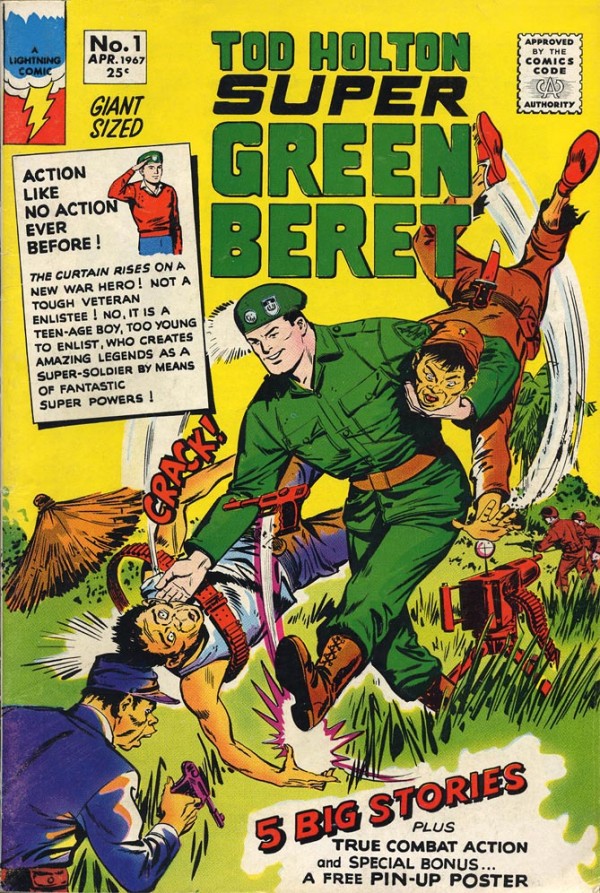

Super Green Beret

Read all his adventures here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu May 09, 2013 -

Comments (7)

Category: War, Comics, Teenagers, 1960s

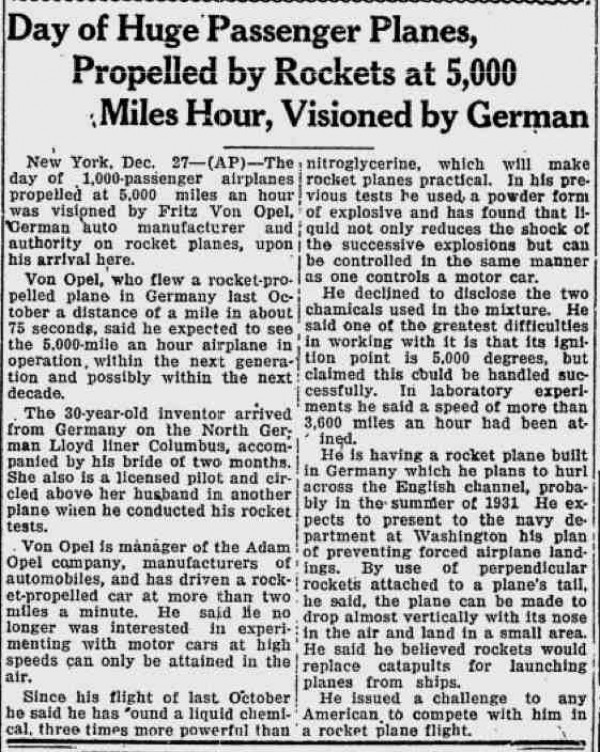

Fritz von Opel

Fritz von Opel was one of those early-20th-century rocket-besotted guys who pioneered this exotic means of propulsion. Just look at his rocket car go in the film clip above! (Narration in German, but not necessary to comprehension.)

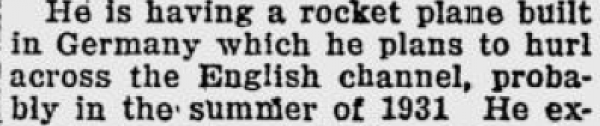

But von Opel's innocent excitement had its darker side. I give you the 1929 newspaper article below. Specifically, the enlarged sentence.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Mar 29, 2013 -

Comments (7)

Category: Inventions, War, Space Travel, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, Europe, Cars

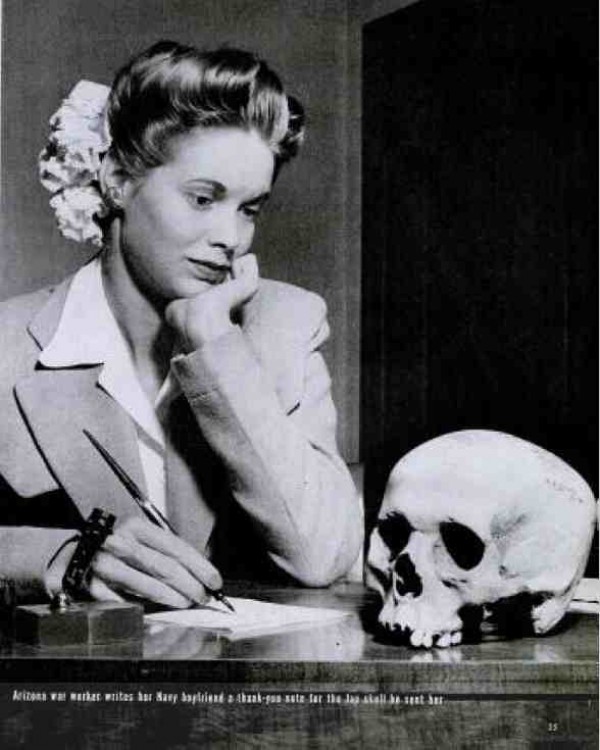

Japanese Skull War Trophy

[Click this text to enlarge.]

Original picture here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jan 05, 2013 -

Comments (10)

Category: War, 1940s, Asia, Skulls, Bones and Skeletons, Love & Romance

WWI German Soldiers Found 94 Years After Shelling

Buried under the dirt of an explosion and almost perfectly preserved since there was no air and water, many of the soldiers were in the same positions as the time of the bombing. Some were sitting up and one was lying in bed. Some pages of a newspaper in the shelter were still readable. There were even the remains of a goat, which has been speculated was used for fresh milk.Here's a shot of the site, being excavated for a road project.

The soldiers were part of the 6th Company, 94th Reserve Infantry Regiment and include Musketeer Martin Heidrich, 20, Private Harry Bierkamp, 22, and Lieutenant August Hutten, 37.

Here's the link to the story in The Telegraph:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/9074336/German-soldiers-preserved-in-World-War-I-shelter-discovered-after-nearly-100-years.html

Ninety-four years is a long time to sit and wait to be found.

Posted By: gdanea - Sat Oct 13, 2012 -

Comments (2)

Category: War

Kayser the Spy

The Reverend Kayser sounds like a real piece of work. German propagandist, adulterer, real-estate conman, and possible saboteur. A man accumulates a lot of possible murderers with that resume.

Bonus points for being named "Kayser" during World War I.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Aug 23, 2012 -

Comments (7)

Category: Death, Real Estate, Religion, Sexuality, War, Weird Names, 1910s

Follies of the Mad Men #182

"World War II was won by superior American staples. We're not saying that just because we make and sell them."

The personal bonus: Bostitch is a company from my home state of Rhode Island.

Original ad here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon May 14, 2012 -

Comments (5)

Category: Business, Advertising, Products, Engineering and Construction, Technology, War, 1940s

Stop That Tank!

Disney creates terrorist training films! I'm sure al-Qaeda is watching this to learn how to stymie our forces in Afghanistan.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 16, 2012 -

Comments (6)

Category: PSA’s, War, Armed Forces, Weapons, Cartoons, 1940s

The Bat Bomb

A few weeks ago, Paul posted about a plan the U.S. military cooked up during WWII to destroy Japan by triggering volcanic explosions. The article below describes a similarly mad plan -- the Bat Bomb. The idea was to strap incendiary devices to bats, and then drop the bats on Japanese cities.I scanned the article from the Atlantic Monthly, December 1946. I think this was one of the first public descriptions of the bat bomb.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Mar 08, 2012 -

Comments (9)

Category: Animals, War, Weapons

Urine Bread

During the Second World War, prisoners held by the Japanese in an internment camp in Dutch Indonesia subsisted primarily on dry bread they made themselves in a camp bakery. But when their captors stopped supplying them with yeast, it became impossible to keep making the bread — until some of the inmates who were trained chemists figured out it was possible to use urine as a yeast substitute.

In the video above, Pieter Wiederhold, who was held in the camp as a boy with his father, discusses this urine bread. He gives a longer account of it in his book, The Soul Conquers:

The absence of bread was most disappointing. Some creating chemists in our camp got together to think about an alternative way to make yeast. After much discussion and some experimentation, they came up with a solution. They would make yeast using urine. When I heard about it I was surprised but not particularly disturbed. After all, I had eaten frogs and lizards that had been cooked in our soup and I had drunk filthy water from a toilet on the train. Why would it kill me if I ate bread that was made with yeast derived from urine? When he heard about it Father smiled. "As long as I have something to eat to stay alive," he said.

In order to provide the entire camp with bread, a large volume of urine was needed every day. A number of large drums were placed in several locations around the camp and each carried a sign:

"Do your Duty. Think of the yeast factory.

By 8:00 AM we must have at least two

full drums or there will be

no bread tomorrow."

Some internees were given the job of collecting the filled urine drums and replacing them with empty ones. They made the rounds using a two-wheeled cart with handlebars like the one I had used for my moving tasks in the women's camp. The drums were taken to the bread kitchen where they were put on large wood-burning firest to cook. Nitrogen had to be kept inside the urine, which was then transformed to ureum, which in turn converts to ammonia carbonate. The nitrogen was then removed. The resulting residue could be used as a substitute for yeast. The project was directed by someone who we called the "chief urinist."

The first time I received my allocated piece of this bread I was pleasantly surprised. It did not look much different from the way it was before, and bringing it to my nose I did not detect any unusual smell. It tasted OK, although we were so hungry that almost everything seemed palatable. The uniqueness soon wore off and no one gave it any further thought. The bread was baked in this manner throughout the rest of our internment in Cimahi.

In Life of Pee: The Story of How Urine Got Everywhere, author Sally Magnusson explains the chemistry:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Feb 29, 2012 -

Comments (7)

Category: Food, War, Body Fluids

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |