The Anomaly That Wouldn’t Go Away

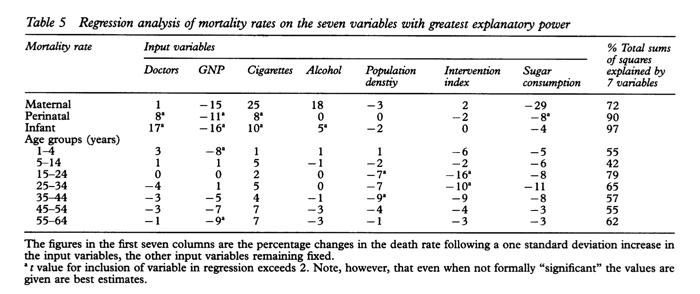

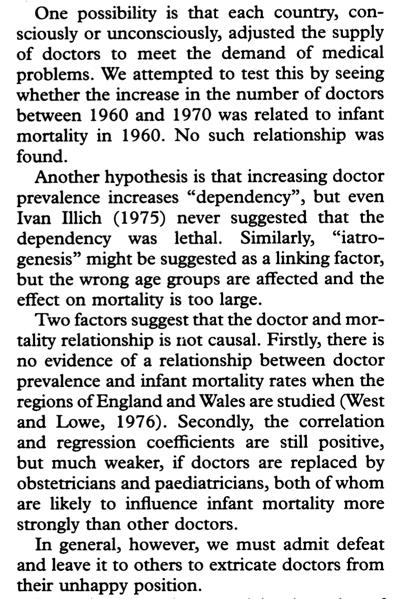

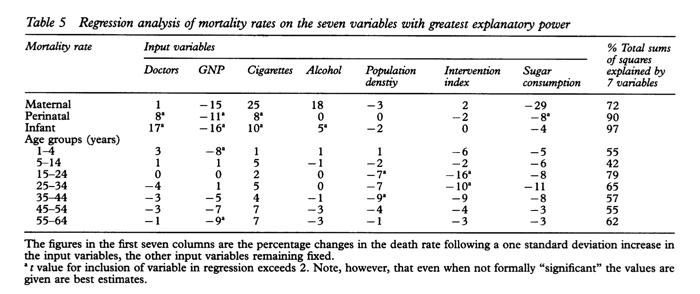

In medical literature, the "anomaly that wouldn't go away" refers to a finding published in 1978 by a group of Welsh doctors (Cochrane, St Leger, and Moore). They had set out to examine the relationship between health services and mortality in the major developed countries, but in doing so they came across a correlation that surprised them — the more doctors there were per capita, the higher was the rate of infant mortality.

The correlation wasn't a weak one. In fact, for infant mortality it was the strongest correlation in their study. The number of doctors per capita seemed to have a stronger negative impact on infant mortality than did the level of cigarette or alcohol consumption in the population.

Obviously the researchers found the correlation unsettling since, ideally, more doctors should result in fewer, not more, infants dying.

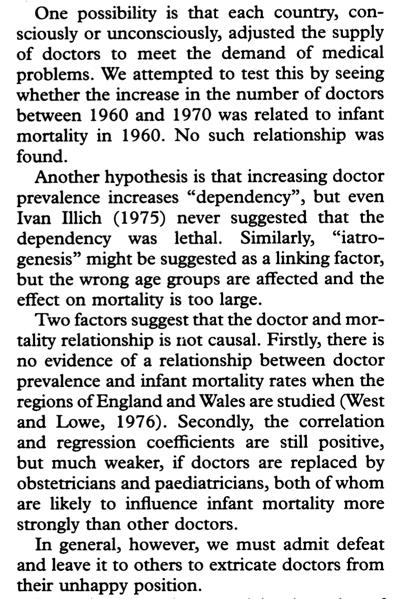

So why would more doctors correlate with higher infant mortality? The three doctors did their best to figure this out:

As the above passage indicates, they didn't think it was plausible that doctors themselves were somehow responsible for the elevated infant mortality, but nor could they come up with a satisfactory explanation for the correlation. So they called it "the anomaly that wouldn't go away."

I'm not sure if the correlation still holds true. I believe it still did about twenty years ago. Unfortunately much of the relevant literature is locked behind paywalls.

Over the years there have been quite a few attempts to explain the anomaly. I've listed two below. Again, I'm not sure if one has been accepted as THE explanation. So the anomaly may still persist.

More info (pdf): Cochrane, Leger, & Moore, "Health service 'input' and mortality 'output' in developed countries."

The correlation wasn't a weak one. In fact, for infant mortality it was the strongest correlation in their study. The number of doctors per capita seemed to have a stronger negative impact on infant mortality than did the level of cigarette or alcohol consumption in the population.

Obviously the researchers found the correlation unsettling since, ideally, more doctors should result in fewer, not more, infants dying.

So why would more doctors correlate with higher infant mortality? The three doctors did their best to figure this out:

As the above passage indicates, they didn't think it was plausible that doctors themselves were somehow responsible for the elevated infant mortality, but nor could they come up with a satisfactory explanation for the correlation. So they called it "the anomaly that wouldn't go away."

I'm not sure if the correlation still holds true. I believe it still did about twenty years ago. Unfortunately much of the relevant literature is locked behind paywalls.

Over the years there have been quite a few attempts to explain the anomaly. I've listed two below. Again, I'm not sure if one has been accepted as THE explanation. So the anomaly may still persist.

C Buck & V Bacsi, "The doctor anomaly," Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1979, 33:307.

It occurred to us that some of the countries richly endowed with physicians may obtain their large supplies by having bigger medical schools, larger classes, and thus less individual instruction of the medical student. The consequence could be a poorer standard of medical practice, the influence of which would be evident in the mortality of the younger age groups where the outcome of disease is most susceptible to the physician's skill.

It occurred to us that some of the countries richly endowed with physicians may obtain their large supplies by having bigger medical schools, larger classes, and thus less individual instruction of the medical student. The consequence could be a poorer standard of medical practice, the influence of which would be evident in the mortality of the younger age groups where the outcome of disease is most susceptible to the physician's skill.

F.W. Young, "An explanation of the persistent doctor-mortality association," Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2001, 55:80-84.

The explanation proposed here is that, as compared with other regions, the expectation of opportunities in the growing industrial cities initially attracts an over supply of doctors. Once in practice, doctors in new regions enjoy fewer economies of scale, which means that they are more numerous as compared with the mature regions. These same industrialising cities attract rural immigrants whose health habits and supports break down in the context of city life. Thus, the places with the most doctors also have the highest death rates, but the two variables are associated only by common location.

The explanation proposed here is that, as compared with other regions, the expectation of opportunities in the growing industrial cities initially attracts an over supply of doctors. Once in practice, doctors in new regions enjoy fewer economies of scale, which means that they are more numerous as compared with the mature regions. These same industrialising cities attract rural immigrants whose health habits and supports break down in the context of city life. Thus, the places with the most doctors also have the highest death rates, but the two variables are associated only by common location.

More info (pdf): Cochrane, Leger, & Moore, "Health service 'input' and mortality 'output' in developed countries."

Comments

I bet they can mandate a shot for that.

Posted by ResortDog on 12/24/22 at 10:08 AM

Probably some combination of more at-risk infants making it through the entire pregnancy in developed areas, and less stringent mortality reporting procedures in less developed areas… i.e., do less developed areas go through the process of birth and death certification with the same rigor as a well developed area? I don’t really know, the cops pulling over the speedy yellow cars might have a better answer.

Posted by SDNAVYVET on 12/24/22 at 05:14 PM

I don't know if it's still true, but you used to be able to chart student SAT scores by state alongside teacher salaries. It showed quite clearly that the more you pay teachers, the dumber the kids were. That's quite the anomoly!

Posted by Phideaux on 12/24/22 at 05:43 PM

@SDNAVYVET: Yes, that's a large part of it.

There used to be a stat that claimed that more infants died in the Netherlands than anywhere in Europe (fueled, of course, by neo-Con American anti-social-medicine industripropaganda). On closer inspection, what happened was a. what you describe, and b. in other countries, doctors were more desperate to keep babies alive until they left the hospital and weren't their problem any more. When they ran the statistics on survival of children past the first year, rather than past the first two months, my country did rather better than most. But if you looked at it with a Randian filter, we were baby-eating devils.

There used to be a stat that claimed that more infants died in the Netherlands than anywhere in Europe (fueled, of course, by neo-Con American anti-social-medicine industripropaganda). On closer inspection, what happened was a. what you describe, and b. in other countries, doctors were more desperate to keep babies alive until they left the hospital and weren't their problem any more. When they ran the statistics on survival of children past the first year, rather than past the first two months, my country did rather better than most. But if you looked at it with a Randian filter, we were baby-eating devils.

Posted by Richard Bos on 12/25/22 at 07:06 AM

I had a grad school roomie who was majoring in statistics, and he had a book titled "How To Prove Anything with Statistics." Each section would begin with some stats -- typically a table -- and these would be used to prove something. Then they would use the same numbers to prove the opposite concept.

Posted by Virtual in Carnate on 12/25/22 at 07:10 AM

For the SAT scores, the answer is that it takes a higher salary to convince a teacher to teach in a school in an impoverished areas with "difficult" students, and those students tend to have low SAT scores.

Posted by Yudith on 12/25/22 at 02:33 PM

@Yudith -- In densely populated areas, all students took the test because it was administratively simpler. In less dense areas, places which traditionally have a lower cost of living, only those students who were potentially headed to college took it because it saved money.

Posted by Phideaux on 12/25/22 at 03:13 PM

@Yudith @Phideaux Probably a combination of both, plus some other confounding factors. (I could speculate, for example, at children of rich parents not needing to bother to study as hard because they'd get into daddy's Alma Mater anyway.)

Posted by Richard Bos on 12/26/22 at 07:08 AM

could it be more doctors = more reports?

Posted by Dana L Battenfield on 12/29/22 at 04:00 AM

Commenting is not available in this channel entry.

Category: Babies | Death | Medicine