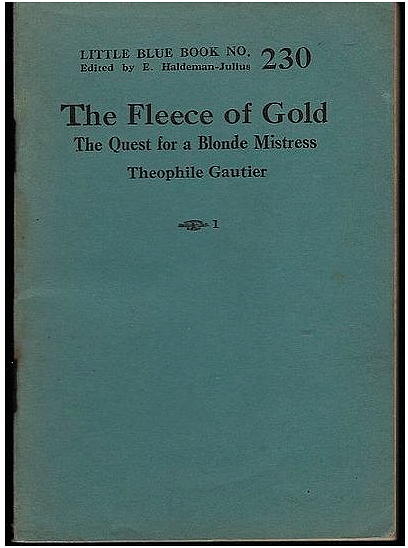

The Quest For A Blonde Mistress

Publisher Emanuel Haldeman-Julius debuted his "little blue books" in 1919. These were cheaply bound, pocket-sized literary and academic works designed to make highbrow culture accessible to the masses. They sold for five cents each.

Haldeman-Julius didn't do this for charity. He wanted to sell as many titles as possible, and to achieve this he would often alter the titles to make them more appealing to consumers. Basically, he would sex up the titles.

For example, he added the subtitle "The Quest for a Blonde Mistress" to Theophier Gautier’s novel The Fleece of Gold. Sales leapt from 6000 to 50,000 copies a year. (Apparently, 'quest for a blonde mistress' is an accurate description of the book's plot.)

Other titles that benefitted from a title change:

• "The Tallow Ball" by Guy de Maupassant became "A French Prostitute's Sacrifice."

• None Beneath the King by José Zorrilla became None Beneath the King Shall Enjoy This Woman.

• Victor Hugo’s The King Amuses Himself became The Lustful King Enjoys Himself.

Haldeman-Julius didn't always make the titles more risque. Sometimes he emphasized self-improvement, and that also had a positive effect on sales. For example, sales of Thomas De Quincey’s Essay on Conversation jumped when it was renamed How To Improve Your Conversation. Similarly, Arthur Schopenhauer’s Art of Controversy became How to Argue Logically. And Dante and Other Waning Classics became Facts You Should Know About the Classics.

Haldeman-Julius was totally open, even boastful, about this strategy. From his book The First Hundred Million:

Haldeman-Julius didn't do this for charity. He wanted to sell as many titles as possible, and to achieve this he would often alter the titles to make them more appealing to consumers. Basically, he would sex up the titles.

For example, he added the subtitle "The Quest for a Blonde Mistress" to Theophier Gautier’s novel The Fleece of Gold. Sales leapt from 6000 to 50,000 copies a year. (Apparently, 'quest for a blonde mistress' is an accurate description of the book's plot.)

Other titles that benefitted from a title change:

• "The Tallow Ball" by Guy de Maupassant became "A French Prostitute's Sacrifice."

• None Beneath the King by José Zorrilla became None Beneath the King Shall Enjoy This Woman.

• Victor Hugo’s The King Amuses Himself became The Lustful King Enjoys Himself.

Haldeman-Julius didn't always make the titles more risque. Sometimes he emphasized self-improvement, and that also had a positive effect on sales. For example, sales of Thomas De Quincey’s Essay on Conversation jumped when it was renamed How To Improve Your Conversation. Similarly, Arthur Schopenhauer’s Art of Controversy became How to Argue Logically. And Dante and Other Waning Classics became Facts You Should Know About the Classics.

Haldeman-Julius was totally open, even boastful, about this strategy. From his book The First Hundred Million:

It is really amazing what the change of a word may do. The mere insertion of a word often works wonders with a book. Take the account of that European mystery of intrigue and political romance, which Theodore M. R. von Keler did for me under the title of The Mystery of the Iron Mask. This title was fair. It certainly tells what the book is about. But there is something aloof about it. It may, says the reader to himself, be another one of those poetic titles. It may fool me, he thinks, and so he bewares. But I changed it to The Mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask, and now there can be no question, for the record is 30,000 against 11,000 copies per year. Two other "slight" additions come to mind. Victor Hugo's drama, The King Enjoys Himself (Rigoletto; translated by Maurice Samuel), and Zorilla's, the Spanish Shakespeare's, None Beneath the King (translated by Isaac Goldberg) were both rather sick—8,000 for the first and only 6,000 for the second. In 1927, lo and behold, the miraculous cure of title-changing brought 34,000 sales for None Beneath the King Shall Enjoy This Woman, and 38,000 for The Lustful King Enjoys Himself! Snatched from the grave! Then there was Whistler's lecture, fairly well known under the title Ten o'Clock. But readers of Little Blue Books are numbered by at least ten thousand for each title yearly. Due to the concentrated interest shown in self-education and self-improvement this helpful lecture on art should be read widely—following this reasoning, the proper explanatory title evolved into What Art Should Mean to You. Readers are more interested in finding out what art should mean to them than in discovering what secret meaning may lie behind such a phrase as "ten o'clock." In 1925 the old title sold less than 2,000; in 1927, the sales, stimulated by The Hospital's service mounted to 9,000.

Comments

Sometimes it is better to change or embellish a title on a work in order to help catch a reader's eye. I think I've come across one or two of those little blue books over the years but until now didn't realize their significance.

Of course, there must be some restraint in making an embellishment on a title - it looks to be easy to venture into parody if one is not careful.

Of course, there must be some restraint in making an embellishment on a title - it looks to be easy to venture into parody if one is not careful.

Posted by KDP on 07/07/20 at 09:21 AM

To wit: Steal This Book, by Abbie Hoffman. Although "sales" probably isn't the best word to describe the way copies moved.

Posted by Virtual in Carnate on 07/07/20 at 11:16 AM

Titles are my bane (well, that and Editors rejecting my work without reading it, and cover letters, and descriptions without descending into technical specs, and not doing enough BTC, and . . . ), so I'm always interested when I run across examples of books which might not have sold quite so well under their original title.

They Don't Build Statues to Businessmen . . . became . . . Valley of the Dolls

Trimalchio in West Egg . . . became . . . The Great Gatsby

The Sea-Cook . . . became . . . Treasure Island

John Thomas and Lady Jane . . . became . . . Lady Chatterley's Lover

Something that Happened . . . became . . . Of Mice and Men

The Un-Dead . . . became . . . Dracula

Zounds, He Dies . . . became . . . Farewell, My Lovely

What's That Noshin' on My Leg . . . became . . . Silence in the Water . . . became . . . Leviathan Rising . . . became . . . Great White . . . became . . . The Shark . . . became . . . Jaws

. . . and of course, the one everybody knows . . .

Pansy . . . became . . . Milestones . . . became . . . Tote the Weary Load . . . became . . . Tomorrow is Another Day . . . became . . . Ba! Ba! Black Sheep . . . became . . . Gone with the Wind

They Don't Build Statues to Businessmen . . . became . . . Valley of the Dolls

Trimalchio in West Egg . . . became . . . The Great Gatsby

The Sea-Cook . . . became . . . Treasure Island

John Thomas and Lady Jane . . . became . . . Lady Chatterley's Lover

Something that Happened . . . became . . . Of Mice and Men

The Un-Dead . . . became . . . Dracula

Zounds, He Dies . . . became . . . Farewell, My Lovely

What's That Noshin' on My Leg . . . became . . . Silence in the Water . . . became . . . Leviathan Rising . . . became . . . Great White . . . became . . . The Shark . . . became . . . Jaws

. . . and of course, the one everybody knows . . .

Pansy . . . became . . . Milestones . . . became . . . Tote the Weary Load . . . became . . . Tomorrow is Another Day . . . became . . . Ba! Ba! Black Sheep . . . became . . . Gone with the Wind

Posted by Phideaux on 07/07/20 at 07:11 PM

Commenting is not available in this channel entry.

Category: Literature | Books