Animals

The Chimpomat

In one of our recent posts, there was a reference to the Chimpomat, a token-operated vending machine for chimpanzees created at the Yerkes Laboratories in the 1930s. Here's more info about it.

"Subject Kambi is shown about to drop a token into the slot of the chimpomat to 'purchase' food."

Info from The Ape People (1971) by Geoffrey H. Bourne:

By the process of lengthening the time between which they could earn the reward and when they could actually receive it by using the Chimpomat (by making the Chimpomat available only certain times of the day), the animals could be trained to collect plastic disks, in other words, to work for money. They would store up this money until the time came for them to spend it. Eventually they were trained to earn the money one day and spend it in the Chimpomat the following day.

On these occasions the animals used to walk around clutching their earnings to their breasts, sleeping on them at night so they would not be stolen, and getting very hysterical if any other animal came near their earnings or tried to take any of them away—a very human side of their actuvity and the dawn of ownership of private property and capitalism, a thought that has intriguing implications.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Oct 02, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Science, 1930s

Misdirected amplexus

"Misdirected amplexus" is the scientific term for the curious phenomenon of male frogs attempting to mate with inappropriate objects. Details from the New ScientistFrog mating is often hard to miss. In most species it involves a process called amplexus, in which males grip onto a female tightly for hours or days at a time until the eggs are fertilised. But there are plenty of records of male frogs grappling an unpromising target such as a frog from a different species or a dead individual. One explanation is that such mistakes are more likely to happen in species that breed in large numbers with a low ratio of females to males, and where multiple species occupy the same breeding pond.

I briefly discussed the subject of misdirected mating in the animal kingdom in my book Elephants on Acid. Here's the relevant text:

During the early 1950s, researchers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center surgically damaged the amygdala (a region of the brain) in a number of male cats. These cats became "hypersexual," attempting to mate with a dog, a female rhesus monkey, and an old hen. Four of these hypersexual cats, placed together, promptly mounted one another.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Sep 26, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Nature, Science, Sex

Rare Bird Beauty Contest

Posted By: Paul - Fri Sep 15, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, 1940s

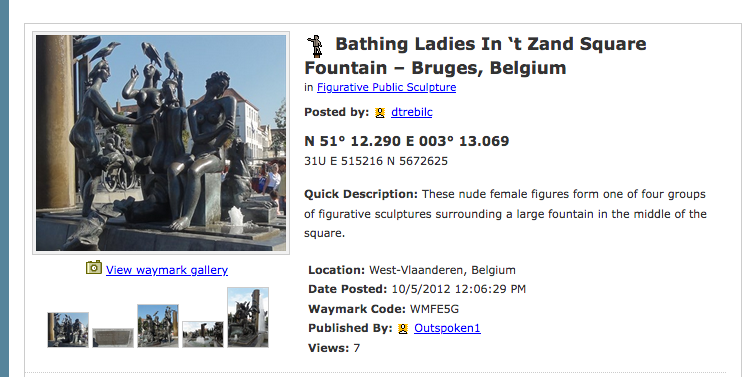

Artwork Khrushchev Probably Would Not Have Liked 52

I must confess to a slight divergence with this entry. All previous ones have featured artwork from within Khrushchev's lifetime, stuff he could have theoretically seen and reacted to. (He died in 1971.) But this one postdates the man.That is all.

Full info here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Aug 31, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Statues and Monuments, Public Indecency, Europe

Hot Testicle Hypothesis

Elephants rarely get cancer. This seems odd because one would think that, elephants being larger than us and thus having more cells, they should be more prone to cancer than we are, not less.Oxford professor Fritz Vollrath has proposed the "Hot Testicle Hypothesis" to explain this mystery.

The gist of the hypothesis is that elephants have unusually hot testicles for a mammal. Their hot testicles result in more mutations in their sperm. So the elephants have evolved more mutation-suppressing mechanisms in their cells. In particular, they have more copies of "p53 encoding genes" than we do, and these genes play a role in repairing damaged DNA.

More info: technologynetworks.com

Posted By: Alex - Sun Aug 27, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Science

Herbivorize Predators

The Herbivorize Predators organization was founded "with the goal of discovering how to safely transform carnivorous species into herbivorous ones." Its members believe that this will promote the well-being of all sentient beings and prevent the suffering and untimely deaths of prey animals.They acknowledge that their mission is controversial but feel that "now is the time to conduct research on potential ways of herbivorizing."

It's certainly an ambitious goal. I think they'll have their hands full just trying to herbivorize humans.

Another critique from the Ecology for the Masses blog:

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 19, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Clubs, Fraternities and Other Self-selecting Organizations, Food, Vegetarians and Vegans

Follies of the Madmen #570

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 12, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Anthropomorphism, Advertising, Air Travel and Airlines, 1970s

Aleck the deluded gander

Details from Life magazine (May 18, 1953):

I haven't been able to find any info about what became of Aleck after the Life article made him famous. How long did he live? According to google, geese in captivity can sometimes live for as long as 40 years. So Aleck might have been standing guard by that oil drum for many years.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 05, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Husbands, Marriage, 1950s

Rodeo Sweetheart

The earliest reference I find to a "Rodeo Sweetheart" is 1929. And the tradition is still flourishing today.To get in the mood for appreciating this longtime contest, you can listen to the classic Byrds album.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 03, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Animals, Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Regionalism, Twentieth Century, Twenty-first Century, Circuses, Carnivals, and Other Traveling Shows

Struck by falling sheep

We've previously reported about people accidentally struck by suicide jumpers (See Death at the Cathedral). But being struck by an apparently suicidal sheep leaping from a bridge is a novel twist on the phenomenon.

London Daily Telegraph - July 30, 2001

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 19, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Accidents, Animals, 2000s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |