Lawsuits

Thought she could fly like Batman

Breunig later sued for damages, but Mrs. Veith's insurance company offered an unusual defense. It said she wasn't negligent and therefore not liable because she had been overcome by a mental delusion moments before swerving out of her lane. She hadn't been operating her automobile "with her conscious mind."

The insurance company lost the initial case, but appealed, and eventually the dispute ended up before the Supreme Court of Wisconsin (Breunig v. American Family Insurance Co.). There, the court heard the nature of the mental delusion that had gripped Mrs. Veith:

Actually, Mrs. Veith's car continued west on Highway 19 for about a mile. The road was straight for this distance and then made a gradual turn to the right. At this turn her car left the road in a straight line, negotiated a deep ditch and came to rest in a cornfield. When a traffic officer came to the car to investigate the accident, he found Mrs. Veith sitting behind the wheel looking off into space. He could not get a statement of any kind from her.

The court ultimately agreed with the insurance company that a sudden mental incapacity might excuse a person from the normal standard of negligence. It noted that a Canadian court had once reached a similar conclusion: "There, the court found no negligence when a truck driver was overcome by a sudden insane delusion that his truck was being operated by remote control of his employer and as a result he was in fact helpless to avert a collision."

But the Wisconsin Supreme Court then ruled that this excuse didn't apply in Veith's case because she had had similar episodes before. Therefore, she should have reasonably concluded that she wasn't fit to drive.

This case has become an important precedent in tort law, establishing the principle that you can't use sudden mental illness as an excuse if you have forewarning of your susceptibility to the condition.

The case is such a classic that in an issue of the Georgia Law Review (Summer 2005) it was even described in verse:

| A bright white light on the car ahead, Entranced Erma Veith, so she later said. Pursuing that light, a miracle did unfold: Of Erma's steering wheel, God took control. Under the influence of celestial propulsion, Erma now operated by divine compulsion. She met a truck, and responded in scorn: She hit the gas, so she'd become airborne. Why, Erma, would you seek elevation? "Batman!" she replied, "my inspiration!" Moreover, at trial, other evidence of panic: She had previously invoked the Duo Dynamic. Once to her daughter, she had commented: "Batman is good; your father is demented." The law held sympathy for Erma's plight: After all, mankind has long yearned for flight. Soaring above, slipping gravity's attraction, Many have aspired to that satisfaction. Still, the law cautioned, the limits were great: "Was Erma forewarned of her delusional state?" On this issue, the evidence appeared strong: "She had known of her condition all along." She experienced a vision, at a shrine in a park: When the end came, she would be in the Ark. Indeed, she would assist, in sorting them out: Those to be saved, and those not devout. Knowing all this, said the court in conclusion, She might well expect, she'd suffer delusion. In her condition, a state most bizarre, Erma was negligent, to drive a car. And to Erma, a lesson of universal appeal: "Nothing can emulate the Batmobile!" |

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 15, 2016 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, Lawsuits, 1960s

Suit Against Satan

Original text here.

Wikipedia entry here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu May 19, 2016 -

Comments (7)

Category: Really Bad Ideas, Religion, Stupidity, Superstition, Lawsuits, 1970s, Fictional Monsters

Cable Car Nymphomaniac

In 1964, a San Francisco cable car rolled partway down a hill before it came to an abrupt stop, causing a passenger, Gloria Sykes, to bang her head against a pole. Six years later, Sykes sued the railway, claiming that the accident had caused her to develop an "insatiable and uncontrollable desire for promiscuous sex." In other words, she had become a nymphomaniac.

The lawsuit is remembered to this day as one of the most bizarre cases in San Francisco's history. Here we take a closer look at it.

The Accident

Gloria Sykes

The accident happened on September 29, 1964. Skyes was onboard a cable car, near the rear exit, as it climbed the steep Hyde Street incline, away from Fisherman's Wharf. About three-quarters of the way up the hill the cable grip suddenly failed, and the car started to slide backwards.

Thirty-six people were onboard. Sixteen of these managed to jump off the car as soon as they realized something was wrong. That left twenty people, including Sykes.

As the car rolled downhill, it quickly picked up speed, going faster and faster. Sykes screamed out, "Don't panic!"

The car rolled for almost three blocks before the gripman yanked on the emergency brake, causing the vehicle to come to an abrupt, shuddering halt. Passengers went sprawling onto the floor and slammed into seats. Sykes banged her head into a steel pole which, she later told a reporter, "I put a dent in."

Luckily, everyone survived in one piece, although many were banged up a bit. Sykes walked away with two black eyes and many bruises, but otherwise she seemed okay. However, "seemed" was the key word. Although the physical injuries soon healed, the emotional trauma did not go away as easily.

Sues For Damages

The next year, Sykes filed a lawsuit against the municipal railway, asking for $36,000 in damages on account of her injuries. However, her lawsuit got tied up in the legal system and remained unsettled.

So five years later, in 1970, Sykes filed a new suit (Gloria Sykes v. San Francisco Municipal Railway), and now she demanded much greater compensation, $500,000. Through her new lawyer, Marvin E. Lewis, she also introduced the dramatic claim that the accident had transformed her into a sex-addict.

The case, with its irresistible mix of an attractive woman and hypersexuality, immediately grabbed the attention of the media. Headline writers seemed to compete to come up with bad puns to describe it, such as "Sex Transit Gloria" and "A Streetcar-Blamed Desire."

Headline-Grabbing Details

During jury selection, Lewis summarized the case for the prospective jurors, telling them he would present evidence to prove that the 1964 accident had irrevocably changed Sykes's life. Sensational details from this summary soon made national news.

Before the accident, as Lewis told it, Sykes had been a deeply religious, strait-laced young woman — a Sunday school teacher and choir girl — but the accident had radically altered her, causing her to develop an "insatiable appetite for sex."

Lewis described how Sykes chose partners at random "when the vibrations were right." Her desire could be sparked by the "mere meeting of eyes while passing on a street." In the past year alone she had slept with over one hundred men, and recently her cravings for physical contact had begun to extend to other women.

However, said Lewis, these cravings had not been a source of pleasure for her. Instead, it had turned her life into a nightmare. Once trim-figured, she had gained over 20 pounds. She had contracted venereal disease (since cured), had had an abortion, and had even attempted suicide.

In addition, she had become a hypochondriac, imagining heart, lung, kidney, and back problems. All these problems made it difficult for her to keep a steady job.

According to Lewis, Sykes was a miserable woman, and all her miseries had started with the 1964 accident caused by the negligence of the railway.

Choosing The Jury

The lawsuit, in addition to sparking a media frenzy, represented a legal first. There had been previous cases where people had sued because an accident had caused a loss of sexual appetite (impotence or frigidity), but no one had ever sued because of increased sexual desire.

Lewis carefully screened the potential jurors to make sure that none of them had a problem with this central premise of the suit. He asked each one, "Could you believe a cable car accident could make a nymphomaniac of a proper, if attractive young woman?"

As it turned out, only one prospective juror indicated that this seemed implausible, and Lewis promptly dismissed her.

Eventually a full jury was selected, eight women and four men, and the trial was ready to proceed.

The Plaintiff's Case

The trial got underway in early April, 1970. It was presided over by Superior Court Judge Francis McCarty.

In making the case for why Skyes deserved $500,000 in damages, Lewis pursued two lines of argument. First, he brought in character witnesses — friends and acquaintances of Sykes — who testified about the change in her personality before and after the accident. Second, he used expert psychiatric testimony to try to persuade the jury about the reality and seriousness of Sykes's psychological condition.

One of the first to testify was a long-time female friend of Sykes who described how before the accident Sykes had been a "religious, upright girl," but afterwards had begun to have one affair after another.

The friend noted that she had once asked Sykes how she managed to meet so many men, and Sykes had responded that "it was easy. You just go up and talk."

The friend also revealed that Sykes had kept a diary, detailing all her sexual encounters. Despite this diary, Sykes often couldn't remember the last names "and sometimes even the first names" of her partners.

The existence of a tell-all sex diary immediately attracted the interest of the media. Lewis noted that he had received many offers from news organizations eager to print excerpts from it. However, the judge ruled that it had to be kept from the media until the end of the trial. (And it apparently never was published.)

As for the medical testimony, the jury heard from psychiatrists such as Drs. Andrew Watson and Meyer Zeligs, both of whom had concluded that Sykes was "getting no pleasure out of her numerous sexual relationships." Instead, they said, her promiscuity was the result of a search for security.

Lewis concluded by emphasizing to the jury his belief that Sykes suffered from a medical condition caused by the 1964 accident. She had, he said, "a neurosis that is no different from cancer or any other serious disease."

The Defense Responds

Deputy City Attorney William Taylor represented the municipal railway. From the start, he repeatedly dismissed as "unbelievable" the idea that a cable car accident could turn a woman into a nymphomaniac.

To undermine Sykes's case, he made three arguments.

First, he suggested that her nymphomania was caused not by the accident, but rather by birth control pills that she had started taking in 1965. The use of birth control pills, Taylor declared, could cause "promiscuity and unnatural sex drives."

Second, Taylor noted that Sykes had sexual affairs before the accident. Lewis conceded this was true, but insisted that "the episodes were few and were 'affairs of the heart.'"

Finally, Taylor brought in psychiatrist Dr. Knox Finley who testified that Sykes could have developed nymphomania without ever having been in an accident. Finley suggested that in Sykes's mind the accident had become a symbol on which she blamed every difficulty in her life.

Testimony of Sykes

During most of the trial, Sykes herself made no appearance. Lewis said that doctors had advised her that daily attendance would be too stressful.

But three weeks into the trial, towards the end, she finally showed up, took the stand, and testified for two-and-a-half days to a standing-room-only crowd.

Her testimony was surprisingly ambivalent. In response to a question from her lawyer about whether she thought the 1964 crash had given her an irrepressible sex urge, she said, "Mr. Lewis, I find it very difficult to believe that there's a connection between my cable car feelings and this sex urge. I don't know exactly what did it — a lot of things... that all worked together."

This mirrored pre-trial statements Sykes had made to reporters in which she expressed uneasiness about the nymphomania label. For instance, she had said, "I am not a nymphomaniac. After all I've been through I just needed a lot of affection, reassurance and security. And most men are not affectionate unless you become involved with them."

She had also said, "I feel so bad about this whole thing. I know how this must be hurting my family. But this emphasis on sex is all wrong."

These comments suggest that the legal strategy of focusing on her supposed "nymphomania" may primarily have been Lewis's idea, and Sykes only reluctantly weny along with it.

The Verdict

Before the jury left to deliberate, the judge issued a surprise directed verdict declaring that Sykes had suffered "some" injury as a result of negligence. Therefore, the only question left for the jury to decide was how much compensation she should receive. Lewis repeated the demand of $500,000, while Taylor suggested that a far lower number of $4500 would be reasonable.

The jury left the courtroom and came back with their answer eight hours later. Sykes, they said, would receive $50,000.

Headlines trumpeted the news: "Jury Rules Runaway Cable Car Caused Runaway Sex," "Sex-Starved Patient Gets $50,000."

But while it was true that Sykes had received an award, what the headlines failed to convey was that the size of the award was far less than what she had sought. Only one-tenth of it. And most of the award would have to go to legal fees, leaving Sykes with close to nothing.

In this sense, the verdict was not a victory for Sykes. The relatively small size of the award indicated that the jury must have been skeptical about the link between the cable car accident and Sykes's crowded sex life.

The defense attorney said he was "not unhappy" about the verdict.

Lewis tried to spin the outcome as positively as he could. He claimed the decision represented a "legal breakthrough" that established the principle of "psychic damages." But he simultaneously admitted he was disappointed with the amount of the award and said he might appeal. That never happened.

Aftermath

After the trial ended, the case no longer made front-page headlines, but interest in it endured. Throughout the 1970s, numerous references to the case continued to appear in news articles. Journalists often referred to it as the "cable car named desire" case.

There were two main reasons for the fascination with the case. First, it seemed to capture so much of the cultural tension surrounding the "sexual revolution" of the 1960s and 70s. Here was a modest, midwestern girl who moved to San Francisco and got swept up in a new, more hedonistic lifestyle, which ultimately proved too much for her. The case seemed to be as much about the sexual revolution, and the ongoing clash of cultures in America, as it was about a cable car accident.

Second, the case fed into concerns about an increase in frivolous lawsuits. Critics of American legal culture used it as a favorite example, summarizing it as the case of the woman who sued San Francisco claiming a cable car accident had turned her into a nymphomaniac — and won! This was true, but overlooked the fact that she won far less than she had sought. And the damages were for her injuries in general, not nymphomania specifically.

What happened to those involved in the case?

The lawyer, Marvin Lewis, continued to make headlines by specializing in unusual cases that often had a sexual theme. For instance, in 1973 he represented another once-devout woman turned sex-hungry nymphomaniac. His client, Maria Parson, sued a health club for $1 million, claiming that the experience of being locked inside a sauna room had caused her to develop multiple personalities, one of which was highly promiscuous. However, a jury declined to award her any damages.

Sykes dropped out of public view. A search of multiple news archives provides no information about what she did with her life after the trial.

However, interest in her story has continued to the present. So much so that in 2014 it achieved one of the highest honors a weird news story can earn. It got turned into a musical. The production, titled The Cable Car Nymphomaniac, debuted to positive reviews at San Francisco's Fogg Theatre.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 29, 2016 -

Comments (8)

Category: Lawsuits, 1970s

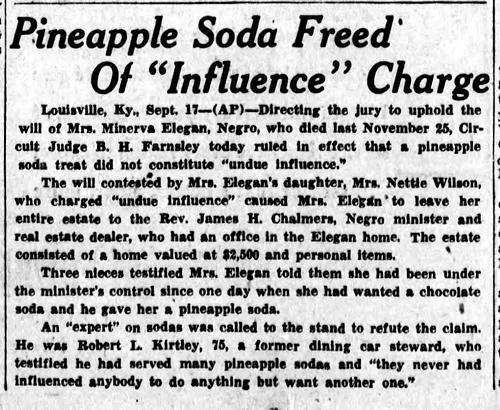

Controlled by Pineapple Soda

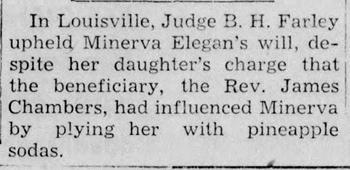

1947: Once Minerva Elagan had accepted a pineapple soda from Rev James Chambers (Chalmers?), she was under his influence forever.

The Daily Standard (Sikeston, Missouri) - Oct 17, 1947

The Cincinnati Enquirer - Sep 18, 1947

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 15, 2016 -

Comments (13)

Category: Lawsuits, 1940s

Square Donuts

The Square Donuts company of Terre Haute, Indiana has been making square donuts for 50 years, and they've trademarked the name. Eleven years ago, the Family Express convenience store also began making donuts that are square, and selling them as "square donuts." The Square Donuts company recently noticed what they were doing. Therefore, lawyers are now involved.Square Donuts demands that Family Express stop selling those square donuts. Family Express insists that "square donuts" is too generic a concept to trademark.

I wonder if anyone has trademarked Triangular Donuts or Polyhedral Donuts? A business opportunity perhaps?

More Info: CBS Chicago

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 29, 2016 -

Comments (11)

Category: Business, Food, Junk Food, Lawsuits

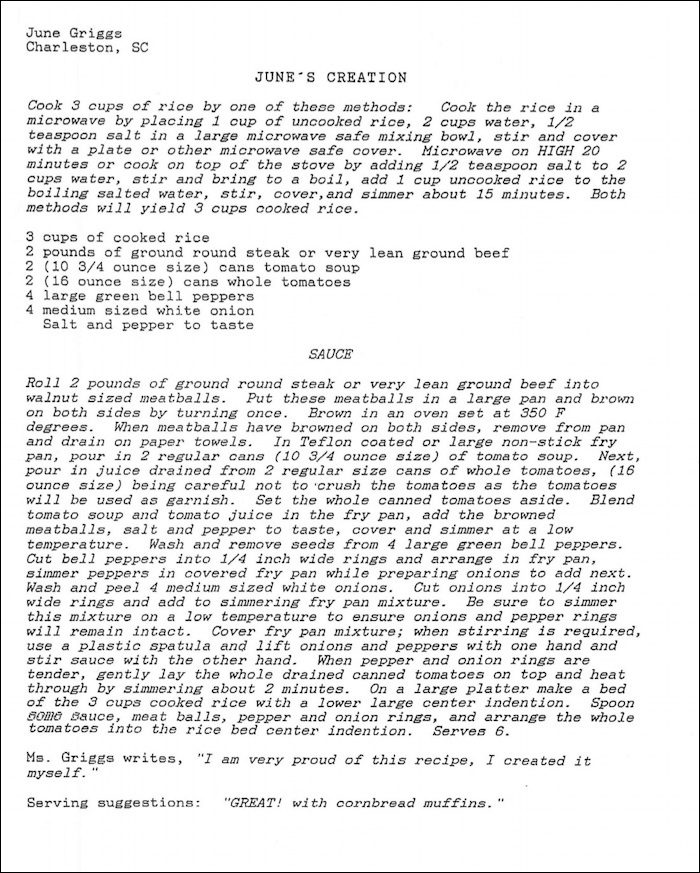

June’s Creation

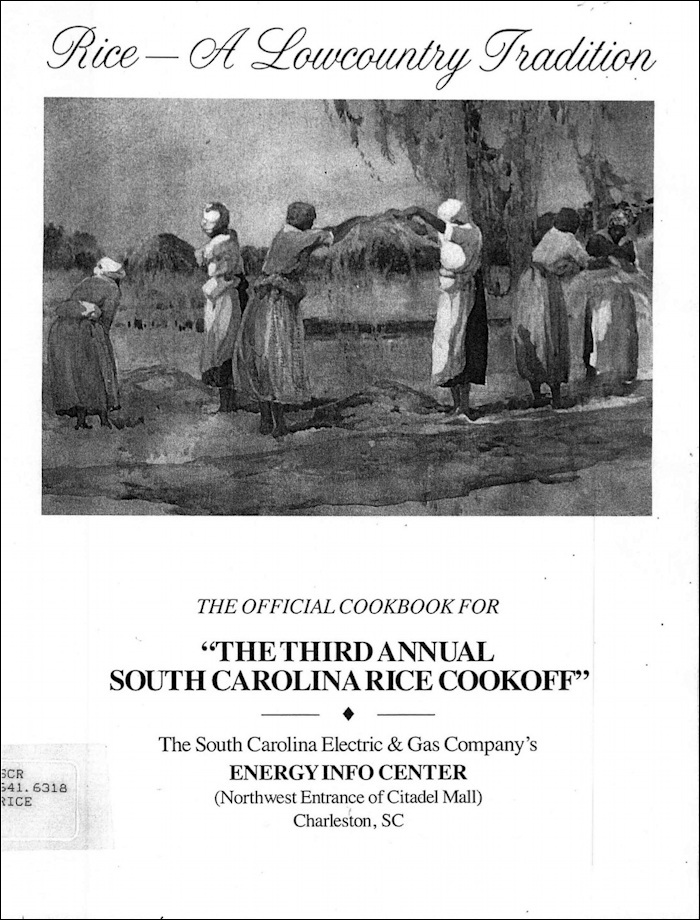

A month ago I posted about the rice recipe that caused a woman to have a nervous breakdown.Summary: In 1989, Bobbie June Griggs submitted her rice recipe to South Carolina Electric & Gas's annual rice cookoff. She didn't win, but they published her recipe in their cookbook anyway. So she sued them, claiming its publication had caused her to have a nervous breakdown. For good measure, her husband sued also claiming "loss of consortium." The case almost made it to the Supreme Court, but they decided not to hear it, thereby letting the previous decisions stand. Those decisions were that: a) you can't copyright a single recipe, and b) "copyright law does not cover infliction of emotional distress." So Bobbie June Griggs was out of luck.

A few of you asked, what was the recipe? Thanks to the magic of interlibrary loan, I finally managed to obtain a copy of it, courtesy of the Charleston County Library, which sent me a photocopy of it free of charge. So here it is — the rice recipe that caused a woman to have a nervous breakdown.

I haven't made it yet, but I plan to try it out sometime in the near future. If any of you make it, let us know how it is, and post a picture of it.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jan 24, 2016 -

Comments (11)

Category: Food, Cookbooks, Lawsuits, 1990s

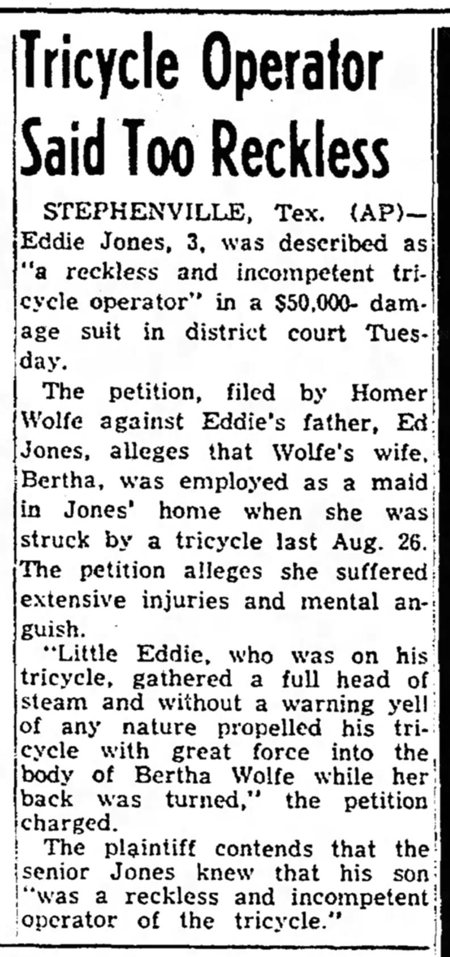

Tricycle operator deemed reckless

It'd be interesting to know what the ruling was in this case, but I haven't been able to find any follow-up articles. The answer is probably hidden somewhere in a court archive.The story reminds me of that more recent case of the aunt who claimed that her 8-year-old nephew's "exuberant hug" broke her wrist, so she sued him for $127,000 in damages. (Yeah, I know, she had to sue for insurance reasons. Perhaps this 1961 case had a similar motive.)

The Daily Capital News (Jefferson City, Missouri) — Jan 27, 1961

STEPHENVILLE, Tex. (AP) — Eddie Jones, 3, was described as "a reckless and incompetent tricycle operator" in a $50,000 damage suit in district court Tuesday.

The petition, filed by Homer Wolfe against Eddie's father, Ed Jones, alleges that Wolfe's wife, Bertha, was employed as a maid in Jones' home when she was struck by a tricycle last Aug. 26. The petition alleges she suffered extensive injuries and mental anguish.

"Little Eddie, who was on his tricycle, gathered a full head of steam and without a warning yell of any nature propelled his tricycle with great force into the body of Bertha Wolfe while her back was turned," the petition charged.

The plaintiff contends that the senior Jones knew that his son "was a reckless and incompetent operator of the tricycle."

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 05, 2016 -

Comments (3)

Category: Lawsuits, 1960s

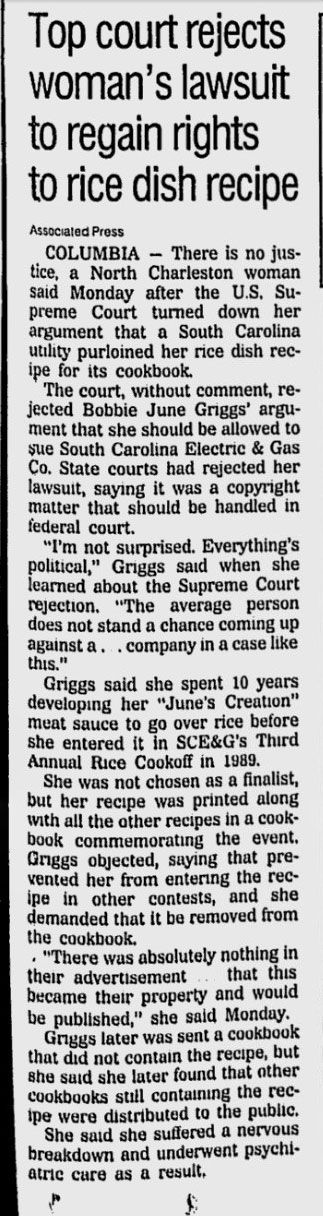

Rice recipe caused nervous breakdown

1992: Bobbie June Griggs sued South Carolina Electric & Gas, claiming that its publication of her rice recipe caused her to suffer a nervous breakdown. Her husband also brought an action for "loss of consortium."Griggs had entered her rice recipe in the utility's Third Annual Rice Cookoff in 1989. She wasn't picked as a finalist, but the utility nevertheless included her recipe in the cookoff cookbook (Rice, a lowcountry tradition: the official cookbook for the Third Annual South Carolina Rice Cookoff). This is what triggered the nervous breakdown.

The state court dismissed her case, noting that it was really a copyright case and thus belonged in the federal courts. In 1995, the state supreme court affirmed this decision (although one justice dissented). And it seems that Griggs tried to take her case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, because the AP reported in April 1996 that the Supreme Court also refused to hear her case, noting that "copyright law does not cover infliction of emotional distress" and also that you can't copyright a single recipe.

Her recipe, which she said she spent 10 years developing, involved canned tomatoes, meatballs, onions and bell peppers on a bed of rice. She called it "June's Creation."

Spartanburg Herald-Journal - Apr 23, 1996

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 18, 2015 -

Comments (10)

Category: Food, Cookbooks, Lawsuits, 1990s

Swimsuit became transparent when wet

Mrs. Muncy of Redondo Beach was shocked and humiliated when her white swimsuit got wet and showed everything. So she sued the maker of the suit for $10,000.Unfortunately I can't find any record of the outcome of her lawsuit.

That info is probably available somewhere in the archives of the L.A. County Superior Court, but their archives aren't searchable online. It's too bad that courts, for the most part, don't make any effort to put their archives online. It would be a gold mine for the history of weird news if they did.

Freeport Journal Standard - Nov 19, 1953

LA Times - Nov 19, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Sun Dec 13, 2015 -

Comments (9)

Category: Lawsuits, 1950s

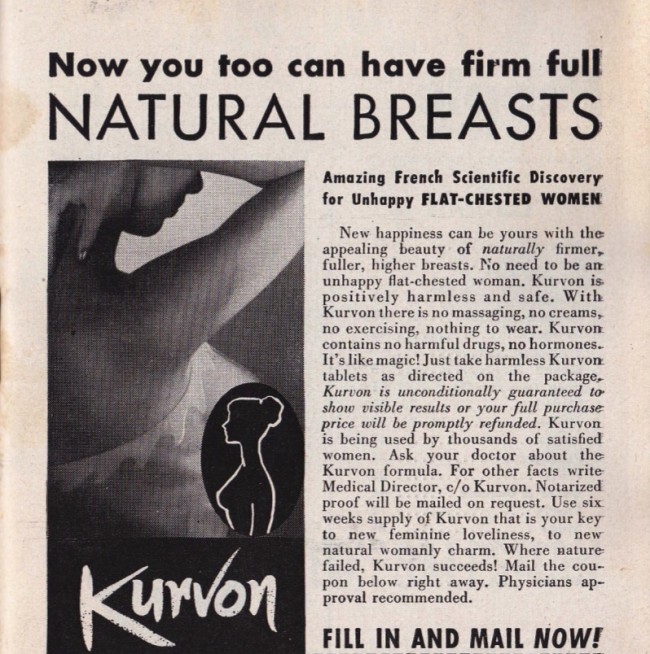

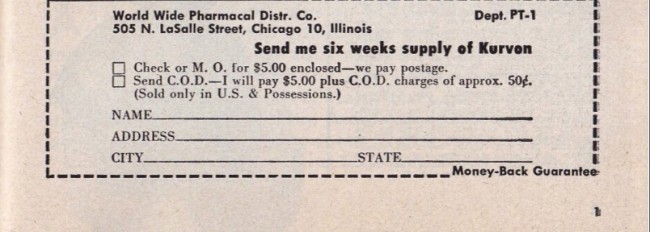

Kurvon Breast Enhancement Pills

[Click to enlarge--ha!]

There's a great story behind this pill, wherein an ex-employee tried to rip off the formula and sell it as "Charm-on." Read it here.

Did you know breast-boosting pills are still for sale?

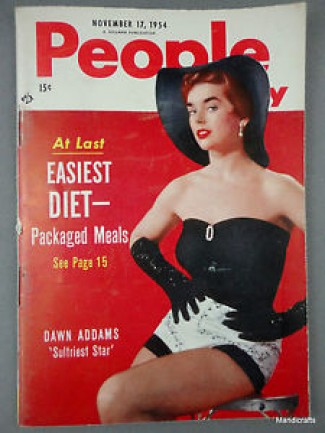

Original ad scanned from this magazine:

Posted By: Paul - Tue Oct 13, 2015 -

Comments (8)

Category: Body Modifications, Lawsuits, 1950s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |